Shakespeare, COVID, and the Plague

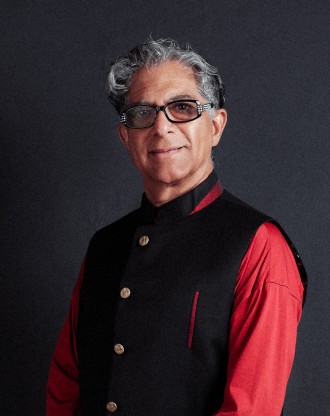

Dr. Deepak Chopra, MD, FACP, founder of The Chopra Foundation, a nonprofit entity for research on well-being and humanitarianism, and Chopra Global, a modern-day health company at the intersection of science and spirituality, is a world-renowned pioneer in integrative medicine and personal transformation. Chopra is a Clinical Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of California, San Diego and serves as a senior scientist with Gallup Organization. He is the author of over 89 books translated into over forty-three languages, including numerous New York Times bestsellers. His 90th book, Metahuman: Unleashing Your Infinite Potential, unlocks the secrets to moving beyond our present limitations to access a field of infinite possibilities. TIME magazine has described Dr. Chopra as “one of the top 100 heroes and icons of the century.

Social isolation gives us time to examine our lives in a new light, suddenly faced with economic collapse, empty streets, current panic, and future uncertainty, and death appearing out of nowhere—in other words, the conditions that confronted every person on a daily basis during the lifetime of Shakespeare. What feels horribly abnormal to us was routinely normal for him and every member of the human race in the 16th century.

In statistical terms, Shakespeare is just another survivor. Unlike his son, Hamnet, who died at 11, Shakespeare didn’t die as a child, nor did his mother die giving birth to him. He also escaped the plague. Ever since the Black Death swept across the globe in the 14th century, bubonic plague remained a threat, killing on average one to three people in every house where it struck. In Shakespeare’s lifetime, there were four plague years, 1582, 1592, 1603, and 1607, when London, including its theaters, shut down because of the disease. Syphilis had arrived in Europe from the New World in 1495, first appearing in a French garrison outside Naples, and it quickly infected every level of society. But Shakespeare didn’t die of it, either, or of smallpox. He wasn’t murdered in the street even though there was no London police force. He couldn’t have been executed as a witch, not being a woman, although the practice was not only current but growing. Finally, unlike his father, John Shakespeare, Will’s life and reputation weren’t ruined overnight due to charges brought against him by Queen Elizabeth’s huge network of internal spies.

As a survivor, Shakespeare stands out because of his genius, but the horrible conditions surrounding him persisted more or less unchanged until the middle of the 19th century. The causes of plague syphilis, and deaths in childbirth started to emerge, and more mundane but equally life-saving advances occurred in public health, like the first sewer system in America, which was built in Chicago in the late 1850s. If humans were simply higher primates with very big brains, survival would be the beginning and end of our story. The Darwinian model for survival requires only getting enough food and finding a willing mate so that you didn’t starve before you were able to pass on your genes to the next generation. Nothing much mattered after that momentous event.

Evolutionists persist in seeing Homo sapiens through the lens of basic survival, but we do all kinds of things to deliberately imperil our survival, from taking care of our weak and sick instead of abandoning them, to stockpiling nuclear warheads, just to make sure that total war can erupt if we feel like it. War, crime, and violence do nothing to improve human genes and in fact work against simple survival. But if you put Shakespeare and the plague together, something mysterious emerges. Despite every threat of disease and death, crime, poverty, political oppression, and religious fanaticism (the Puritans in Shakespeare’s day railed against the London theaters as ungodly, but luckily they didn’t shut them down until 1642, 26 years after his death), not to mention widespread illiteracy, no public sanitation, and no police force, these horrendous circumstances didn’t wipe out creativity, discovery, love, compassion, and a vision of higher ideals.

Homo sapiens is the only species that liberated itself from natural evolution, and this unprecedented achievement involved one thing only: going beyond. Not our higher brain but human nature envisioned life independent of physical circumstances. Miraculously, if you peer at the oldest cave paintings in Europe, such as those in Chauvet-Pont d’Arc, France, you don’t see primitive scratching from 30,000 years ago. You see art. The animals depicted are done with confident, artistic lines that are also scientifically accurate, depicting a wide range of Paleolithic creatures precisely enough that they can be identified by species. No one knows why sophisticated cave paintings suddenly appeared. The Chauvet depictions lie deep in the darkest heart of the caves. No sunlight penetrated, so the painters worked by the quavering light of torches. In addition, since the animals were not right before them, they worked from memory of how each one looked.

This act of going beyond exemplifies a trait that belongs to the human condition, the trait of creativity for its own sake. In fact, even though the modern world owes everything to discoveries that improved life, the rise of technology and all the practical benefits it has brought, going beyond has always happened “in here” before anything could happen “out there.” Before the first primitive flint blades could be hacked out, the concept of “tool” and “weapon” had to come first. And before a concept can be born, there has to be a mind capable of concepts.

My point is that you and I, like our ancestors, are the product not of genetic evolution but the evolution of consciousness. We were liberated from the Darwinian scheme by self-awareness. In other words, we said to ourselves, “I just thought of what I’d like to do,” and with the combination of awareness, vision, and desire, we evolved into the human condition. The Greek word for beyond is meta, and we should apply it to ourselves more often. To be human is an expression of the metahuman. Shakespeare was a meta-genius, but everyday people are just as meta in their own way. Parents sacrifice for their children, even die for them, because they go beyond their own selfish needs. Any creative hobby is meta, because it has nothing to do with surviving. The higher your vision, the more meta you are. Buddha was extraordinarily meta, but his followers, seeing the worth of his vision, had to be meta or Buddha would have preached in the wilderness. Likewise, without metahumans among Jesus’s disciples, Christianity would have perished on the cross.

The COVID virus has put everyday life in peril for countless people, but it has actually risen the level of self-sacrifice, service, sharing, cooperating for the common good, laying down political antagonisms, seeking a global solution, and reflecting upon what really matters. Those are all meta qualities; they are perfect examples of going beyond. The fact that we can see a future past the devastation of the pandemic is a meta trait of huge importance. We aren’t human without being metahuman. For me, this is the lasting lesson and the deeper meaning to be taken away from a terrible time.

Composed by Dr. Deepak Chopra, MD, FACP, founder of The Chopra Foundation